The art of writing big stakes fantasy/sci-fi/superhero/other-genre blockbusters is, to some extent, the art of designing choke points in antagonists’ plans.

The Death Star’s entirely unstoppable, unless one plucky hero can fire a shot down this one vent.

Sauron is a relentless, all-consuming evil, but if you can chuck this ring in this volcano, we can sort the whole thing out.

The Infinity Gauntlet can kill half of everyone in the universe! But if you can get hold of it, you can stop Thanos from using it (or, in a pinch, use it to bring everyone back).

Unstoppable evils create big stakes, but they’re bad drama. Or, rather, they’re bad for your action/adventure drama.

Those scenes in superhero team comics where Thor’s hammer is bouncing off Giant Unstoppable Foe X but Hawkeye is still firing arrows at it are a bit tedious. You need, as a writer, some doodad, some macguffin, some reversible tachyon flow, that allows a single, underpowered protagonist or small team to have agency.

If they get to fight someone on something high up, even better.

Most of us understand this on some level. It makes the rhythms of ‘epic’ genre stories feel familiar, predictable. Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse hangs a hat on this by making the choke point a super boring USB stick and moving on (Chris Pine’s blond Spider-Man just straight up calls it a goober. They’re always goobers to him).

Game of Thrones obscures the choke point by inflating it to become a decade or so of political intrigue and war, and you have to step back a bit to see it. The game of thrones is something that has to be resolved favourably in order for Westeros to get it together in time to fight the White Walkers. But the game of thrones is the story. The White Walkers feel more like a sop to traditional fantasy fans to get their buy-in than the thing George R.R. Martin really wanted to write about.

In the shadow of the Crisis on Infinite Earths, Alan Moore tells his own evil-to-end-all-evil story. For John Constantine and Swamp Thing, the Crisis is just a sideshow that throws everything up in the air enough for the real big bad to take advantage.

The Brujería, a cult of South American warlocks are using the crisis to usher in a primordial darkness from before time to destroy Heaven. This is what Constantine has been warming Swampy up for over the last few stories.

Moore blows through his choke point, the ceremony at which the Brujería will be mustering this ancient evil, in #48, one of the most horror-ish issues of the run so far. We get a great calm-before-the-storm issue that largely consists of Constantine and Swampy getting together two arms of a prototype Justice League Dark, decades before DC realised that putting ‘Justice League’ in the title of any series featuring more than two characters was its second strongest marketing move1.

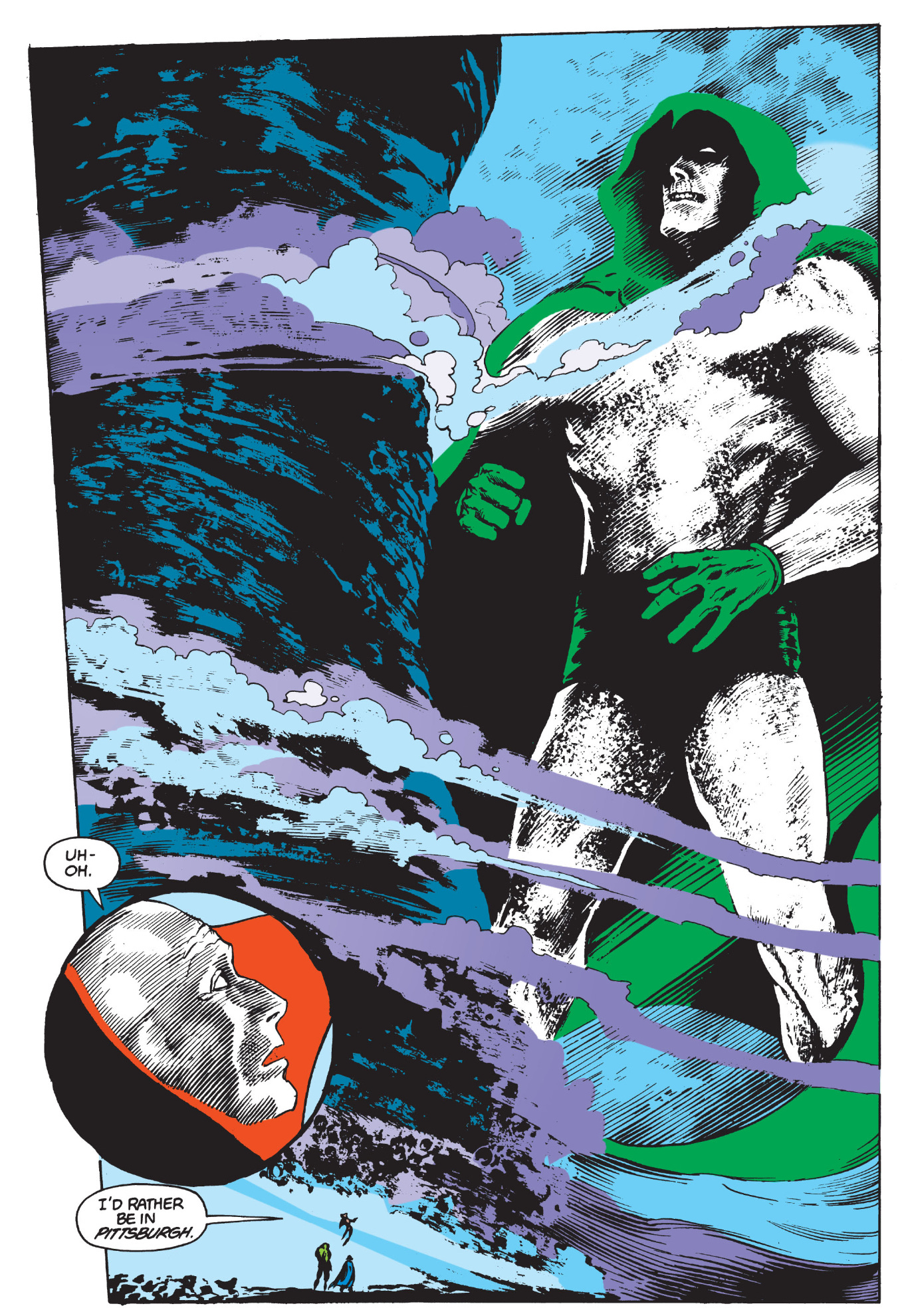

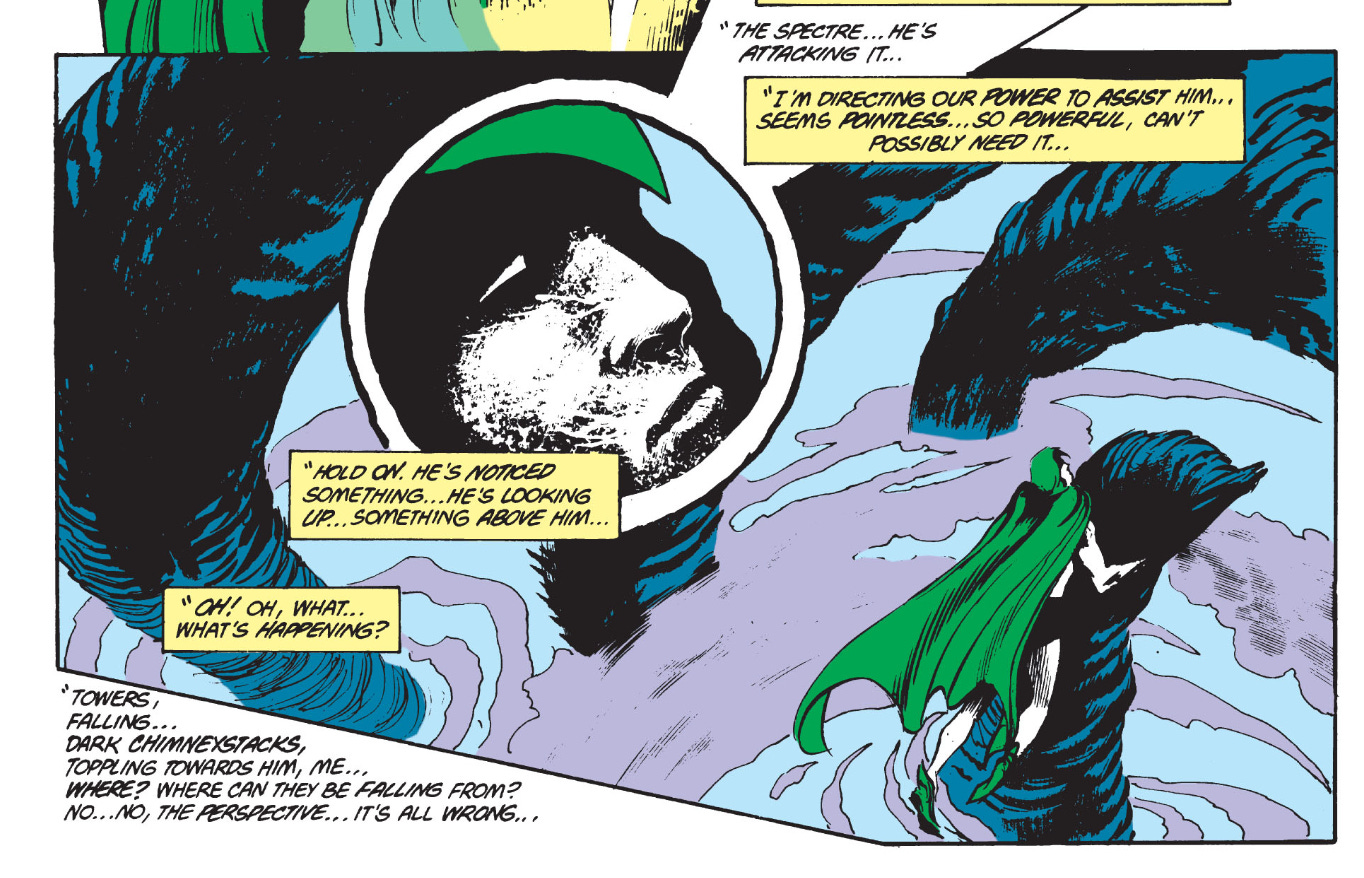

Then comes #50, in which everyone’s facing off against this Lovecraftian cosmic force and you’re wondering whether the plant guy really has much to do other than lob some tubers at it.

Honestly, the whole thing might have been better as a prose piece. One of the advantages of a Lovecraft story2 is that he never really has to get us to visualise a force of evil from beyond creation—he just describes bits of it, and tells us what it isn’t.

Bissette, Veitch and Totleben, for all their strengths as murky horror artists, don’t really do justice to the scale or sheer existential darkness that Moore is trying to get at. It’s tempting to say that it’s impossible to really deliver on what Moore is getting at, in fact, except that I suspect his later collaborator JH Williams III or someone of his ilk might have got there.

Anyway. It’s looking like our guys are going to be left throwing vertebrae at this giant black blob, but the whole thing is actually solved with a bit of philosophy.

More next week.

A link (just one).

A discussion in the comments of Steve Cook’s Secret Oranges substack post about the Stanley Kubrick archive led me to digging around for info on Kubrick’s working practices, and I came across this great piece by Jon Ronson from 21 years ago. It’s a fascinating nosey around the brain of one of the great 20th century filmmakers. Both are worth your time.

(OK, that was two links).

Number one is putting ‘Batman’ in the title.

The disadvantages, of course, being the racism etc.